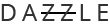

Igor Kostin

The first photographer on site at the Chernobyl reactor in the aftermath of the explosion on April 26th, 1986.

Igor Kostin

Igor Fedorovich Kostin was one of only five photographers permitted to take pictures of the Chernobyl nuclear power plant near Pripyat, Ukraine, in the aftermath of the April 26th, 1986 disaster. At the time, Igor was working as a photographer for the Novosti Press Agency (APN) in Kiev, Ukraine. His aerial photograph of the Chernobyl nuclear power plant was widely published around the world, showing the extent of the devastation, and triggering widespread fear of radioactive contamination caused by the accident, while the Soviet media was working to censor information regarding the accident, releasing limited, albeit falsified information, if any.

“At three hundred meters above the reactor, the radioactivity reached 1,800 roentgens per hour. The pilots were sick during the flight. In order to throw their sandbags into the burning hole of the plant, they stuck their heads out of the cockpit and made a visual guess.”

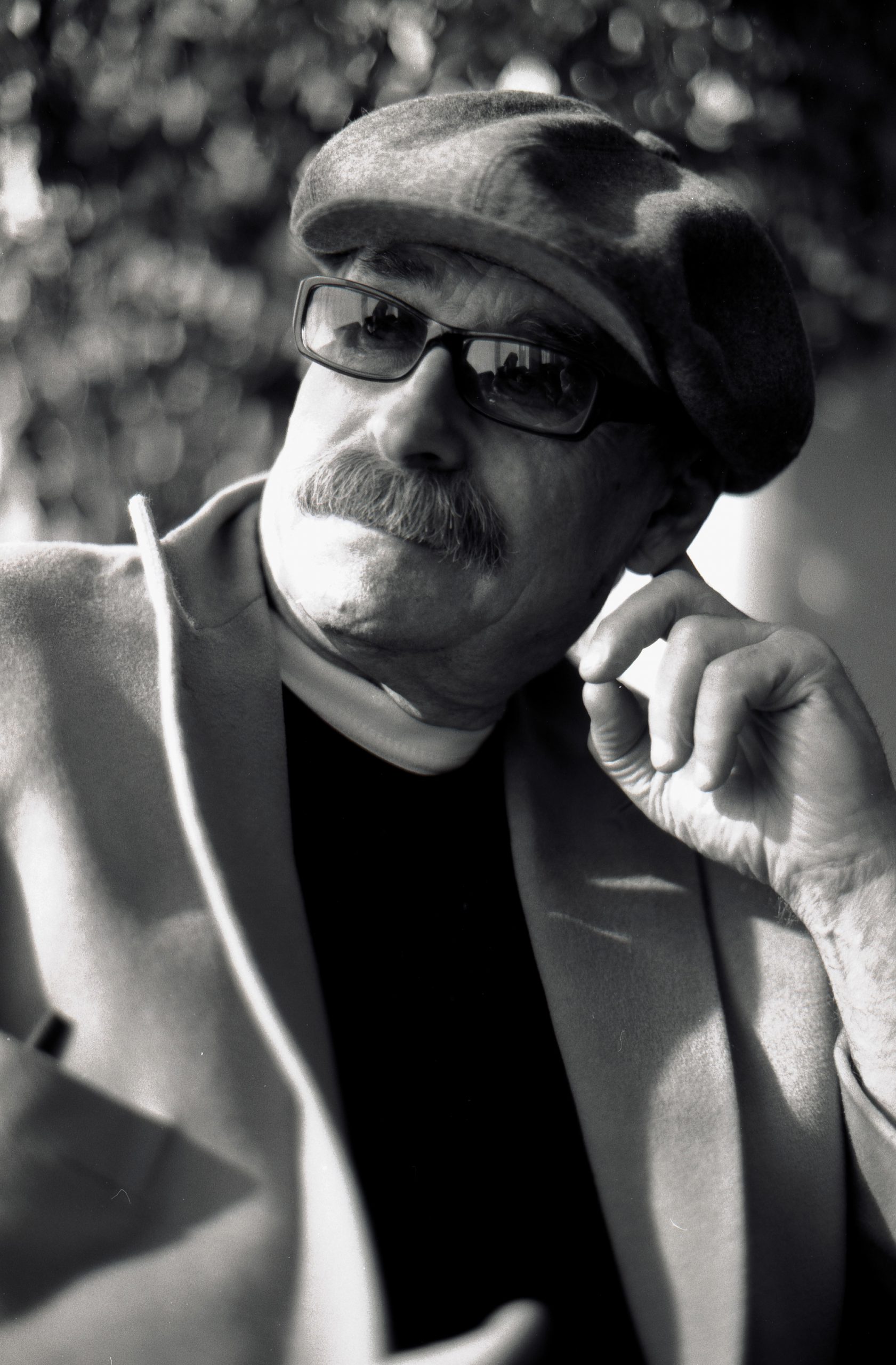

Sergei Vassilievitch Sobolev

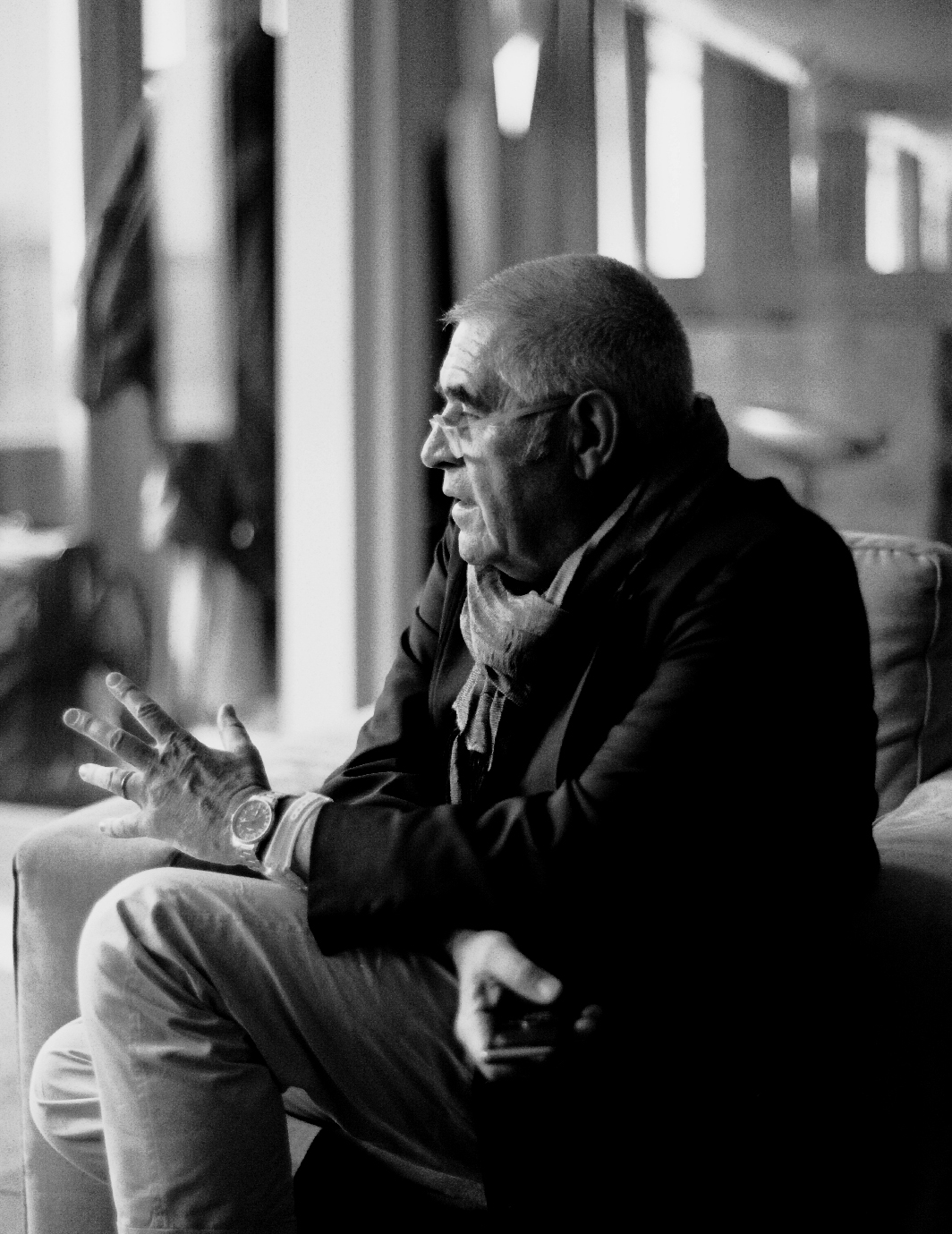

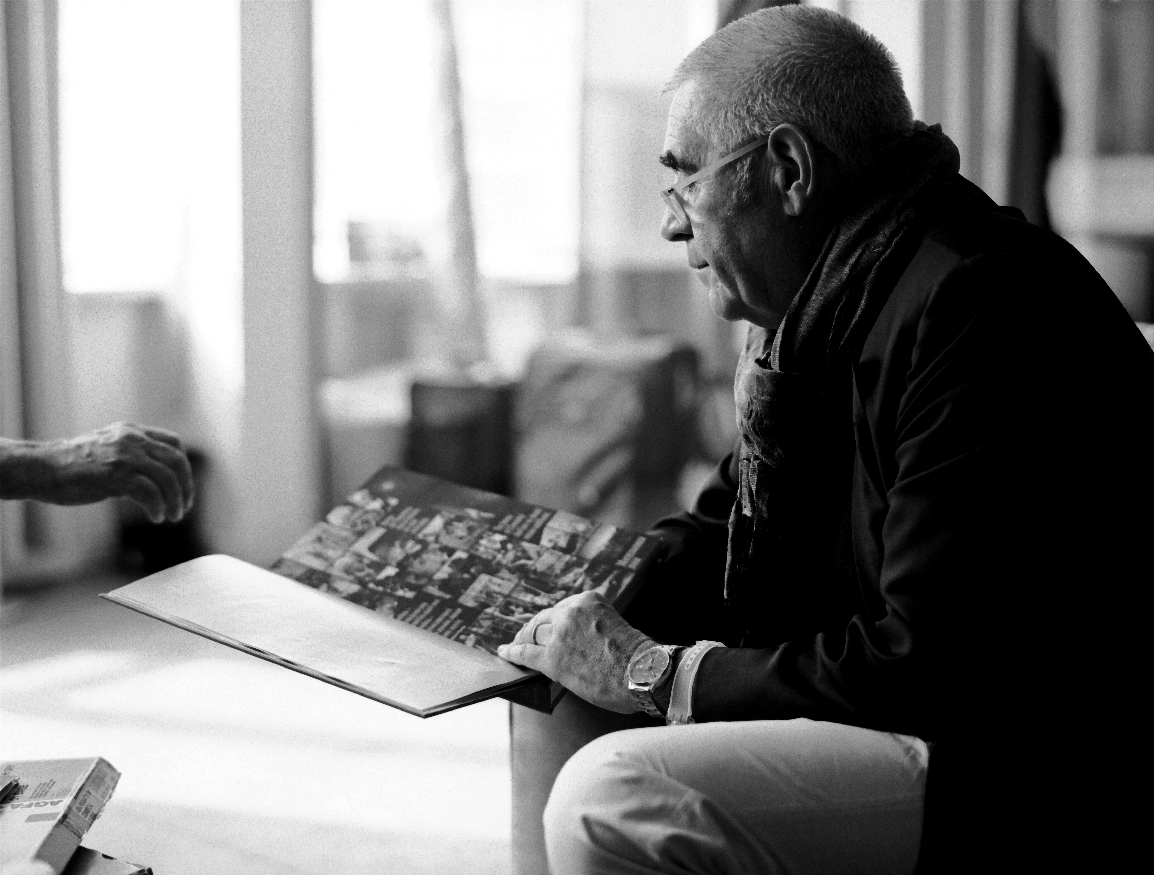

These images were taken during our first meeting at the institute of cinematography in Kyiv, Ukraine. The images include also pictures taken in his mother’s apartment, where Igor kept a lot of photographic prints from the reactor accident.

When I started this project, I quickly learned of Igor Kostin due to his famous damage assessment photograph taken from a helicopter of the NPP. I could not find him for an entire year, he simply seemed to be a ghost. And then, by sheer coincidence, through a friend of a friend, I got his contact information. And then we met.

Igor Kostin

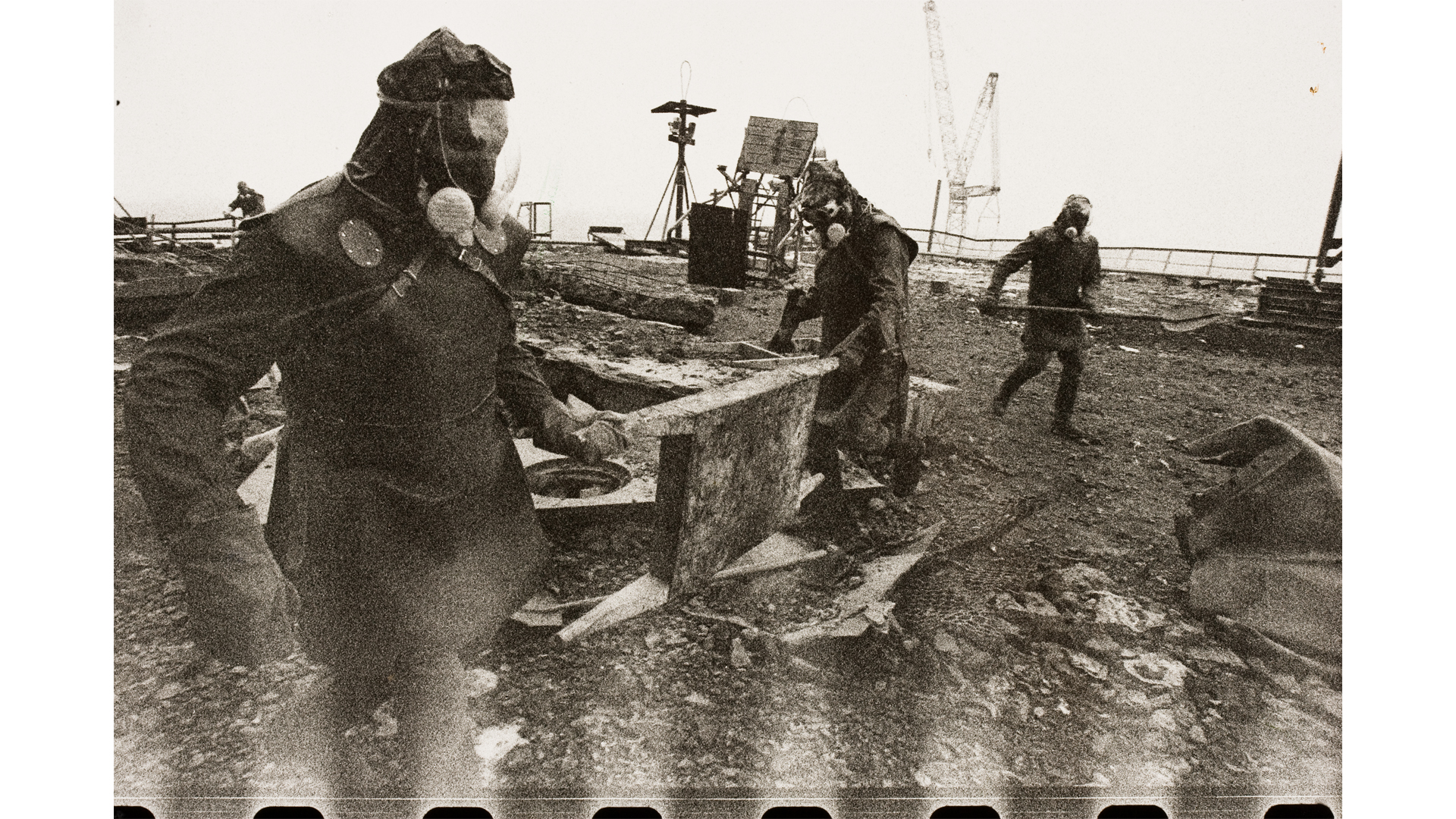

This is a photo Igor gave me. It is remarkable for two reasons. First, at the bottom of the image, where the perforation holes are, one can clearly see the impact radiation had on his film. Originally, when he took the first pictures of the accident site from the helicopter, only the first image was exposed properly, albeit very grainy, but the remaining 35 exposures were see-through. There was nothing on the film. It was clear as glass. Initially, Igor thought his camera malfunctioned until the realised the impact radiation had on his film. Later on he mounted a piece of lead under his camera to counteract the radiation.

And second, the people you see in the photograph were all part of the clean-up process. Through the explosion blown-up pieces of the reactor rods were thrown onto the roof of the adjacent buildings. And that debris was highly irradiated. At first, robots from Germany were used to collect the radioactive rods, but failed. Radiation caused the robots’ CPU to melt down. So it had to be done by hand. These guys in the photo were referred to as the “Roof Cats”, and their mission was a suicide operation. A supervisor monitored the activities, a dosimeter in one hand, in the other a stop watch. The “Roof Cats” were sent out onto the roof for 60 seconds, in that timespan they shovelled as much debris as they could off the rooftop. Then they had to get off the roof and rest for a while. And then repeat the action. Again and again.

Most of the men died of high-radiation poisoning within days.

Igor Kostin

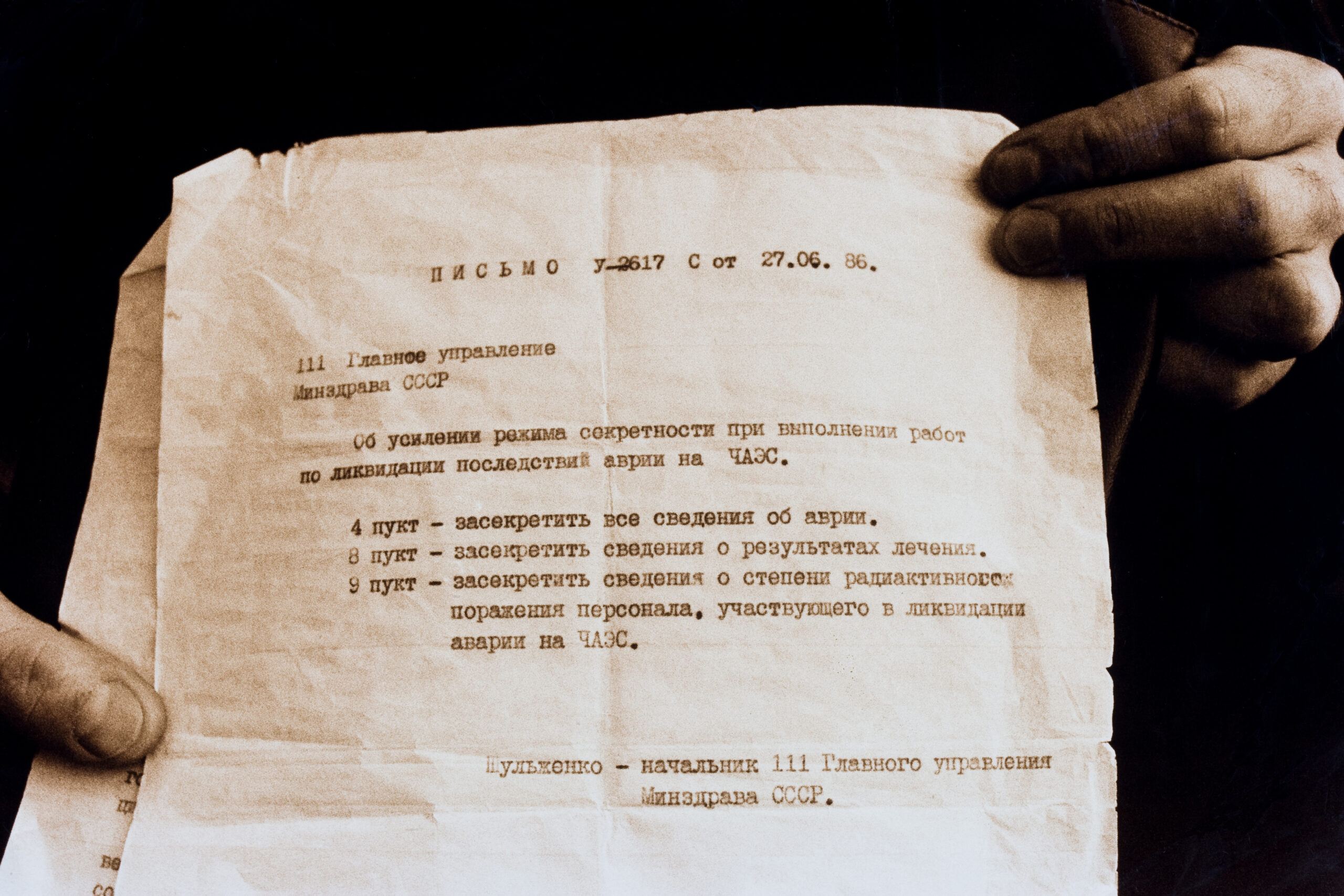

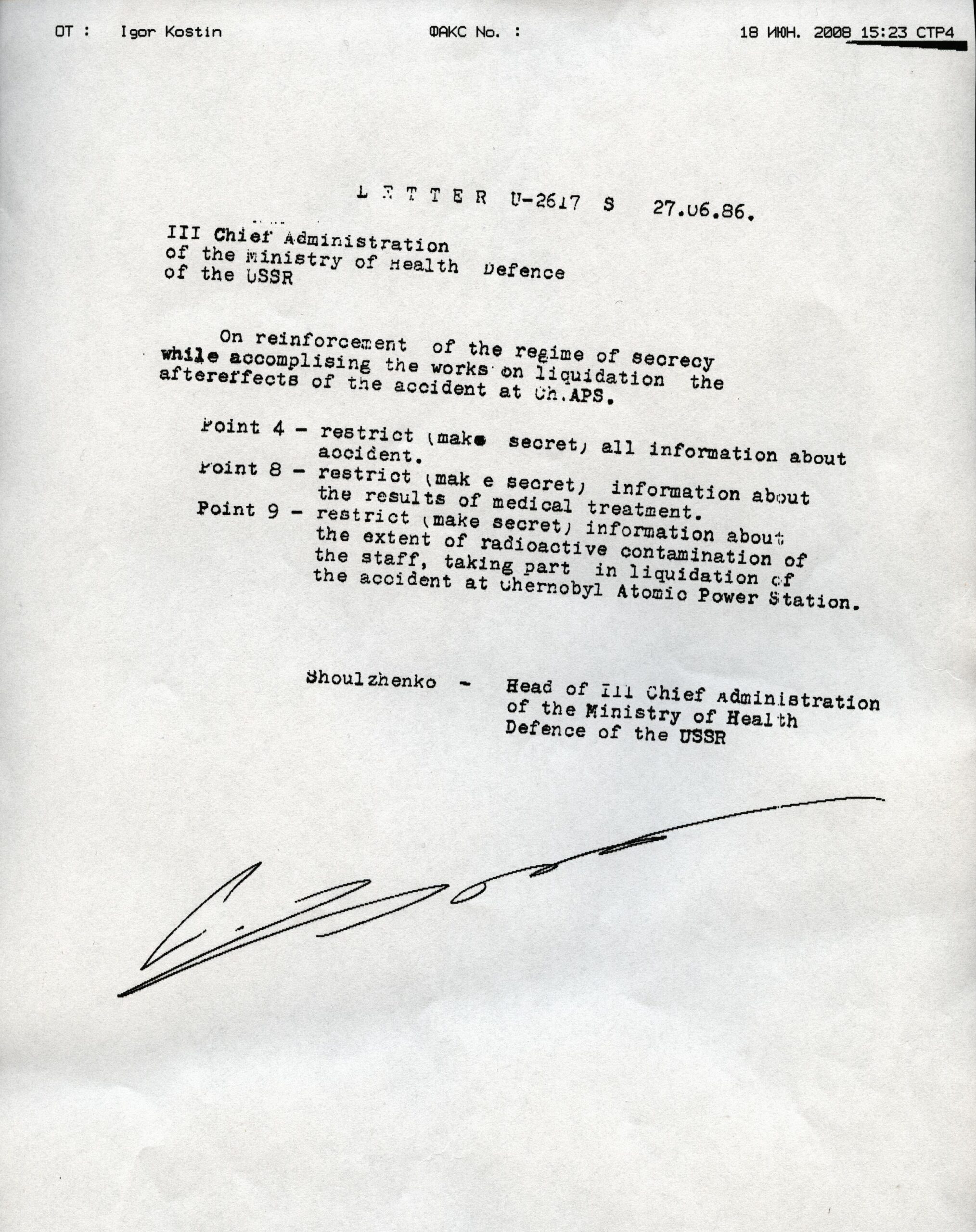

Below is a telling photograph Igor took of a secret Soviet document issued by the Ministry of Health Defence of the USSR. It was published on April 27th, 1986, a day after the power plant accident, at which time the Soviet leadership still strongly denied any such accident occurred. To the left is the photograph, to the right the english translation. Read for yourself.

“What is the cost of lies? It’s not that we’ll mistake them for the truth. The real danger is that if we hear enough lies, then we no longer recognize the truth at all.”

Valery Alekseyevich Legasov. Soviet chemist in charge of investigating the Chernobyl accident.

As evidenced in this photograph, the Russian Administration was keen on anything but telling the truth.

On April 28th, 1986, the alarms at the entrance of the Swedish nuclear power plant at Forsmark were set off. Technicians first thought that a leak inside the plant was the reason for the alarm. But soon they realised that the alarm was triggered by plant employees walking through the radioactivity detector upon entering the facility. So it must have come from the outside, they concluded. After an analysis, they identified the radioactive particles on plant workers shoes as specific to Soviet nuclear power plants. Also, during the previous weekend the wind had blown from the south-east and it had rained in the north-eastern parts of Sweden, depositing radioactive fall-out on the ground in that area. All the evidence was pointing towards one of the nuclear power plants in the Soviet Union. In addition, NASA reported of the Chernobyl explosion by presenting satellite photographs of the event. As international evidence and pressure mounted, the Soviet leadership could no longer deny that an accident had occurred at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant by April 30th, 1986.

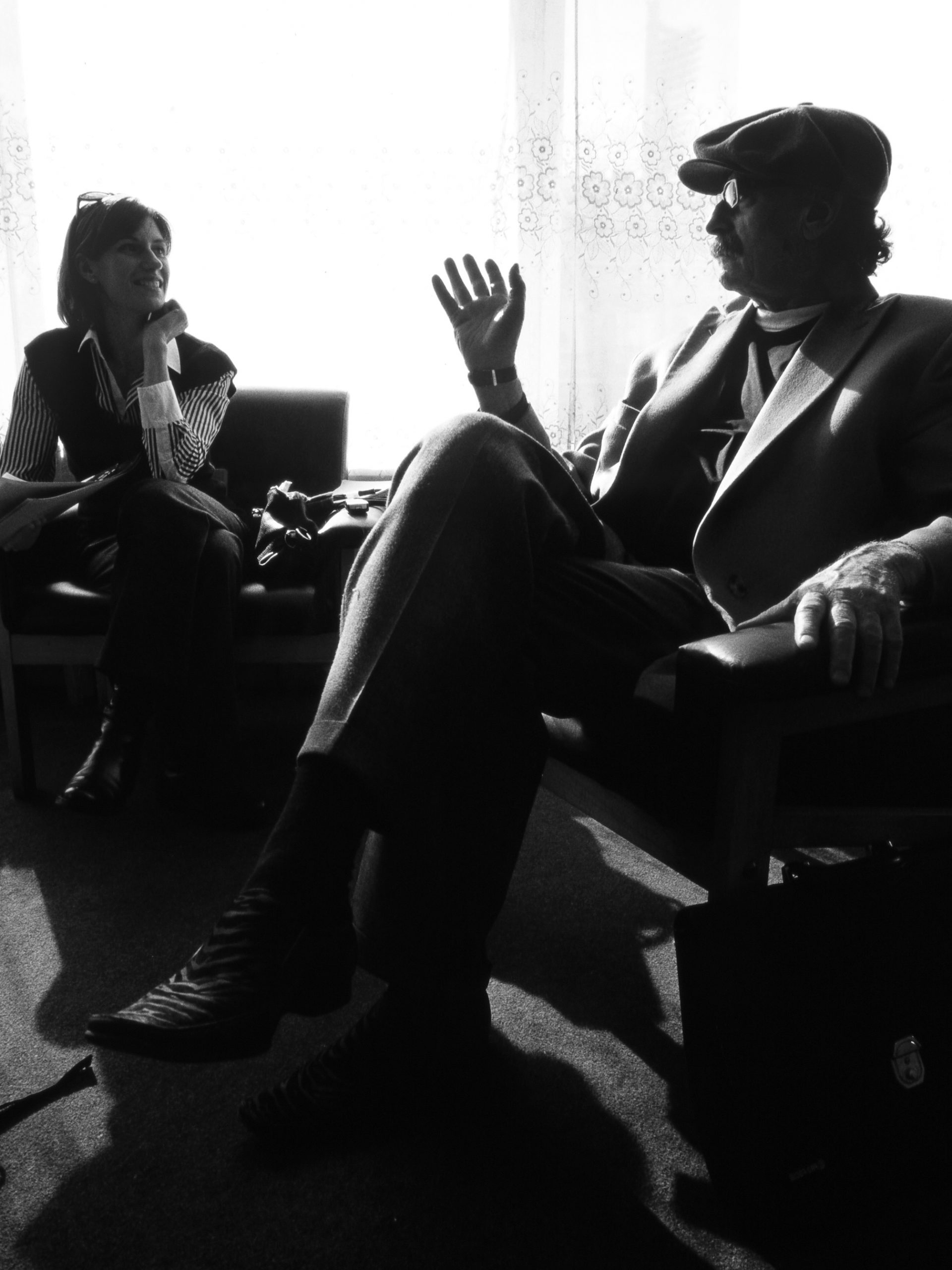

Igor Kostin

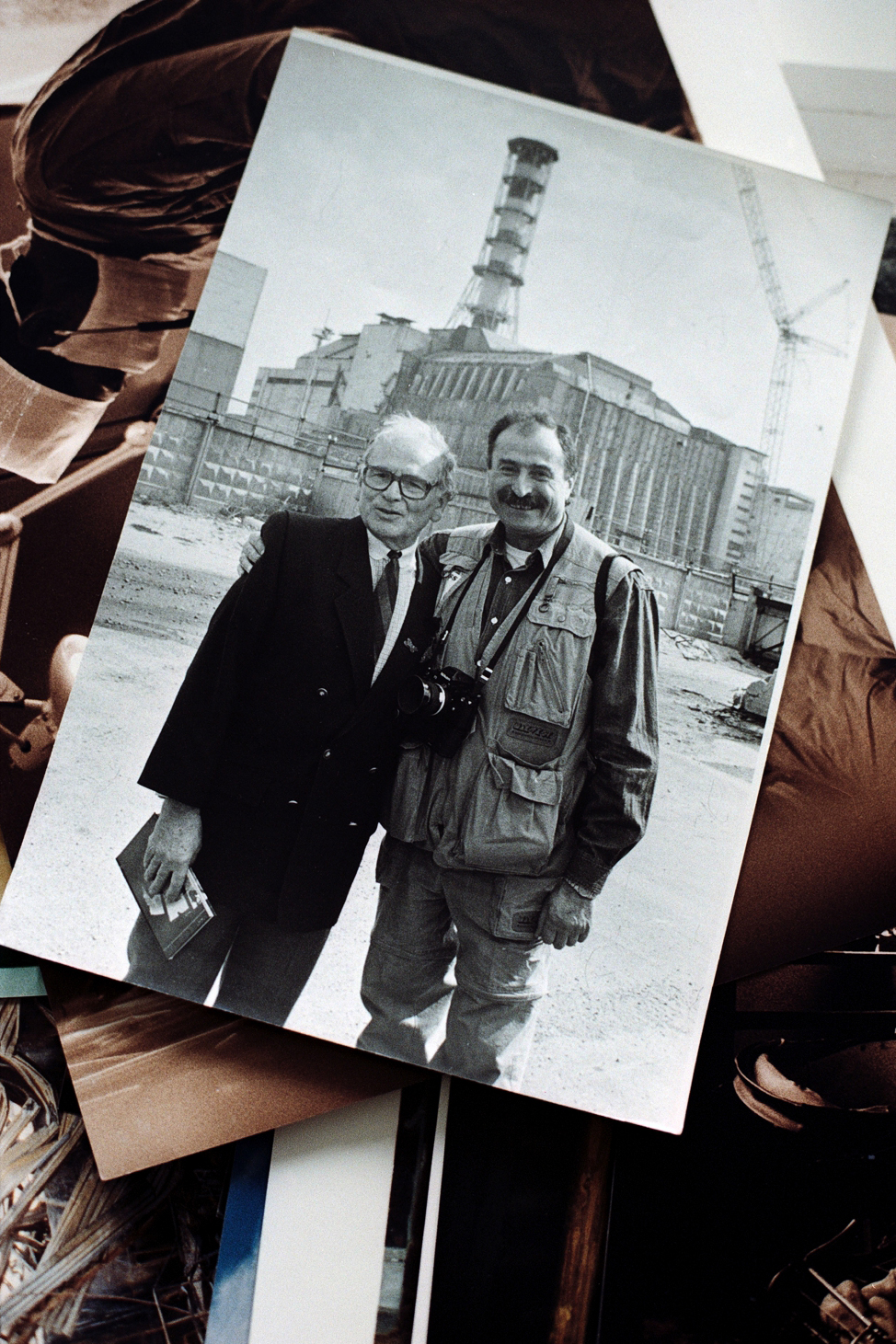

These are images from a meeting between Igor Kostin and Peter Noever. From 1986 to 2011, Noever was Artistic Director and C.E.O. of the MAK (Austrian Museum of Applied Arts / Contemporary Art) in Vienna, Austria. I had approached director Noever about an exhibition of Igor’s photographs of the 1986 NPP accident. And Peter Noever greenlighted the show. Igor never had his photos exhibited, it seemed like the perfect moment in time. The show was supposed to open at the MAK in April of 2011.

Then, for no apparent reason, Igor changed his mind at the end of 2010. He sent an angry telefax in Russian, the operative word in it was нет, нет, нет…No, No, No! And that was the end to that. And then on March 11th, 2011, the world learned about a new nuclear power plant disaster: Fukushima, Japan.

“They were removing the fuel with their hands! And when he [the friend who wrote Igor the letter] came to the social security office and explained that he worked on the roof and asked for money for some medication, they said: “Those people who worked on the roof died a long time ago. Why would you come here and lie?” Do you understand? And he wrote this to me, I have written proof where he wrote: “Igor, is it our fault that we are still alive?”

Igor Kostin, interview excerpt